Third Alfred Packer Confession

Third Packer Confession Letter to D. C. Hatch of Denver Rocky Mountain News 8/7/1897

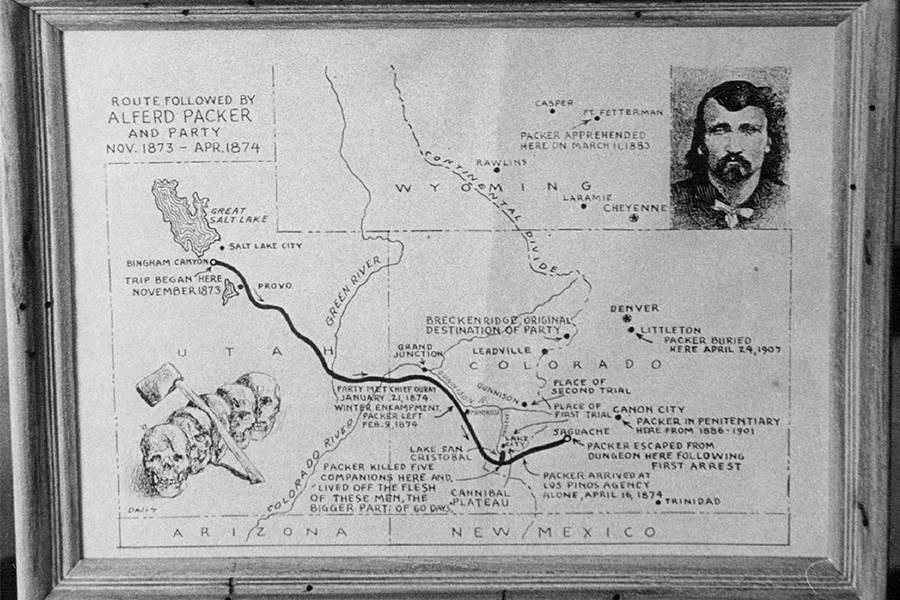

"Mr. D.C. Hatch, 842 Larimer Street, Denver, Colo.: My Kind Friend - Your welcome favor of the 22nd inst. Has been received, and in reply to your request I gladly comply by giving to you as complete a statement as it is possible for me to, viz: In the fall of 1873 a party of men left Salt Lake City by wag on, there being teams and pack animals. In leaving we were deficient in supplies for the entire journey. But this matter can hardly be attributed to either myself or anyone else of the party of twenty-one (21), for the agreement was that the men who owned the teams were to furnish our sustenance. But unfortunately, our supplies were exhausted by the time that we reached the Green River, at the head of the Colorado.

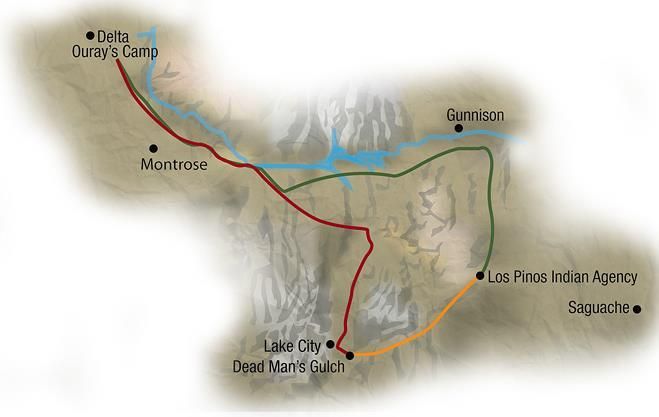

And now, my kind friend let me impress upon you the painful fact that thus early in our journey we were suffering most terrible from the pangs of hunger. For about five days we had been surviving on horse feed, which was chopped barley. Just at this point we ... Ouray and a band of fifty Indians, from whom we received assistance. And, being informed by Chief Ouray that the mountains were impassable, owing to the great amount of snow, we availed ourselves of his invitation and camped within two mile of him, and from whom we purchased supplies. After having been in this camp for about one week a man by the name of Lutzenheiser and four other men started for the agency, having been informed by Chief Ouray that from his camp to the Indian Agency it was forty miles, while in fact, buy air line, it was eighty miles. Lutzenheizer and his party had no other provisions, only what each man carried, they being on foot. As a result, their provisions soon became exhausted. And these five men had concluded to cast lot to see who should be food for the others. But just at this time a coyote was seen, which was immediately killed, and was the means of saving one of that party from a tragical fate. And, as this party neared the cattle camp where Gunnison now stands, Lutzenheiser saw a cow fast in the snow and he crawled up to her and shot her with his revolver. The man who had charge of the cattle, happening to be out looking for his herd saw the tracks which Lutzenheiser had left, and, following these tracks, he soon found Lutzenheiser in an exhausted condition.

He took him into this camp and followed his trail back and found the remaining four of the party, whom he al so took into the camp, a man by the name of George Driver being the last, who was carrying the head of the coyote. Here they remained until they had become physically recruited, when they started for the Los Pinos agency, which was forty miles into the mountains, at which place they were again picked up in a fainting condition. All of which was sworn to at the time of my trial and is a matter of court record. And now I return to my own party, which composed six men, myself included. There being two trails to the agency, about one week after Lutzenheiser's party left, we took the upper trail for the purpose of reaching the same destination.

We also were on foot and carried what provisions we could in blankets. After nine days our provisions were entirely exhausted. The snow being deep, we were compelled to keep on top of the divide, in order to travel at all. And these divides led to the top of the Rocky mountains. Our matches had all been used, and we were carrying our fire in an old coffee pot. Three or four days after our provisions were all consumed we took our moccasins, which were made of raw hide, and cooked them, and, of course, ate them. Our suffering at this time was most intense, such, in fact, that the inexperienced cannot imagine. We could not retrace our steps, for our trail was entirely drifted over. In places the snow had been blown away from patches of wild rose bushes, and we were gathering the buds from these bushes, stewing them, and eating them. In following these divides, we soon gained the tip of the Rocky Mountains, and the snow being blown away from the top of the mountains and our feet encased in pieces of blankets, we were enabled to travel along steadily. Now my friend, you can imagine our condition, on top of the mountains, with nothing to kill for food and not even any of those rose bushes. Starvation had fastened its deathly talons upon us and was slowly but most tortuously driving us into the state of imbecility; in fact, Bell, the strongest and most able-bodied man of our party, had succumbed to the power of mental derangement and was causing the party to be very much afraid of him, as well as that which they felt to be the inevitable doom of each, mentally.

I am at a loss to fully express our feelings at this stage, but we consulted each other and conclude to come down off the mountain. For we could not tell whether we had passed the agency or not, for it was either snowing or blowing constantly. And, as it happened, we descended to the lake fork of the Gunnison river. We camped one night just above the lake. In the morning I ascended the mountain for the next purpose of ascertaining if there were any visible signs of civilization on the opposite side. The snow being very deep, it required the entire day to make this trip and return. As I neared the camp on my return I was confronted by a terrible sight. As I came near I saw no one but Bell.

I spoke to him, and then, with the look of a terrible maniac, his eyes glaring and burning fearfully, he grabbed a hatchet and started for me, whereupon I raised my Winchester and shot him. The report from rifle did not arouse the camp, so I hastened to the campfire and found my comrades dead. Can you imagine my situation - my companions dead and I left alone, surrounded by the midnight horrors of starvation as well as those of utter isolation? My body weak, my mind acted upon in such an awful manner that the greatest wonder is that I ever returned to a rational condition. In looking about, I saw a piece of flesh on the fire, which Bell had cut from Miller's leg. I took this flesh from the fire and lay it to one side, after which I covered the bodies of my dead comrades. I remained here with them during the night. In the morning I moved about 1,000 yards below, where there was a grove of pine trees. I distinctly remember of taking a piece of the flesh and boiling it in a tin cup. I also know that I became sick and suffered most terribly. My mind at this period failed me. But I am satisfied that I must have eaten some of the flesh, but my mind was a total blank for a considerable period of time. When my mind returned I found, by my tracks, that I had been visiting around the adjacent territory, seeking rose buds, which I apparently found, for I noticed that by force of habit I had been stewing them in my tin cup. The record of time now becomes a nonentity. I do not know how long I remained here. I did not know how near I was to the close of the year. I could not tell how near spring was. But the weather began to moderate, and I wandered around seeking rose buds for food, when all of a sudden I was confronted by the Los Pinos agency. It would be a mild assertion for me to say that I was surprised. And most agreeable it was, too. I found out that in my searching for food and civilization I had traveled forty miles from the lake fork of the Gunnison.

For three weeks I was taken care of at the agency. I have learned that Lutzenheiser and his party had crossed the mountains into Siwatch. The remaining of the twenty one men now at the end of this three weeks came through with a band of Indians. They questioned me as to where my comrades were. I replied that I had killed Bell and that evidently he had killed the others. In a day or two we left the agency and started with the teams to go over to Siwatch. We remained in Siwatch until General Adams, the Indian agent, returned from Denver. I then explained to the general all I knew about my dead comrades, and an expedition was fitted out to return and bury them. We had not gone far on this journey before we were compelled to turn back to the agency, owing to

the great depth of snow and the crust which was upon it. After returning to the agency, I was turned over to the sheriff of Siwatch, with whom I remained until the middle of July. At this time the sheriff, Amos Wall, asked me if I could realize what I had passed through. In reply I gave him as complete an explanation as I could, after which he told me to go away and not permit it to longer worry me. I did as he advised, so far as to the going away, and after the lapse of ten years I was arrested in 1885 upon the charge of having murdered my companions. The result of my trial is well known to all; how the supreme court granted me a new trial, and how I was convicted of manslaughter upon five different indictments, tried by one and the same jury, receiving an accumulative sentence of forty years, being eight years for each. Now, my kind friend, in conclusion permit me to say that I am to-day, as ever before, a member of the human family, although isolated and away from that which is dear to the heart of every man. Am I the villainous wretch which some have asserted me to be? No man can be more heartily sorry for the acts of twenty-four years ago than I. I am more a victim of circumstances than of atrocious designs. No human being living can say that I in cold blood, with evil intent, murdered my companions upon that awful occasion.

What could be the object of my taking their lives in a wanton manner? I bear no malice towards living man. Even though I may feel that I have been unjustly dealt with, still that Supremacy which rules over all knows that I forgive as I would wish to be forgiven. In this the darkest hour of my earthly existence I feel, as I have long felt, that I would have far better off had my execution taken place years ago, and I might now be with those companions, whose ghosts, I assure you do not haunt me, for if the soul h as existence beyond this mortal life, each and every one of those unfortunate men knows that I am innocent. As it is there is some unexplainable power which retrains my hand from freeing my soul. Hence all the brightness in the firmament of my earthly future is centered in the hope that I may eventually be given an opportunity of proving to the world that I am "less black than has been painted." And to all my kind friends I can but reiterate that my heart to-day, as before, abounds with thankful gratitude for your many expressions of good will. I should like to be set at liberty under the banner of a pardon, but if that should not be deemed best, I would gladly avail myself of the opportunity that a commute would give of showing that I came into existence under circumstances similar to that of others, and that I still possess a desire to live and do right. O! my friend! Were it not for the flame of hope which forever burns within the human heart, life would certainly be beyond endurance?"

Gratefully Yours, Alfred Packer